“Transformative Politics”

Hey all. Let's hop to it.

Politics

A few days ago, the New York Times ran a guest essay from the historian Timothy Shenk on a lost manuscript Barack Obama and his friend, the economics professor Robert Fisher, drafted in the 1990s. It was for a book that would have been called “Transformative Politics.” Shenk:

Speaking with a candor he would soon be unable to afford, Mr. Obama directed his fire across the entire political spectrum. He denounced a broken status quo in which cynical Republicans outmaneuvered feckless Democrats in a racialized culture war, leaving most Americans trapped in a system that gave them no real control over their lives. Although his sympathies were clearly with the left, Mr. Obama chided liberals for making do with a “rudderless pragmatism,” and he flayed activists — with the civil rights establishment as his chief example — for asking the judiciary to hand out victories they couldn’t win at the polls. Progressives talked a good game about democracy, but they didn’t really seem to believe in it.

Mr. Obama did. With the right strategy, he argued, Democrats could engineer a political realignment that would begin a new chapter in the country’s history.

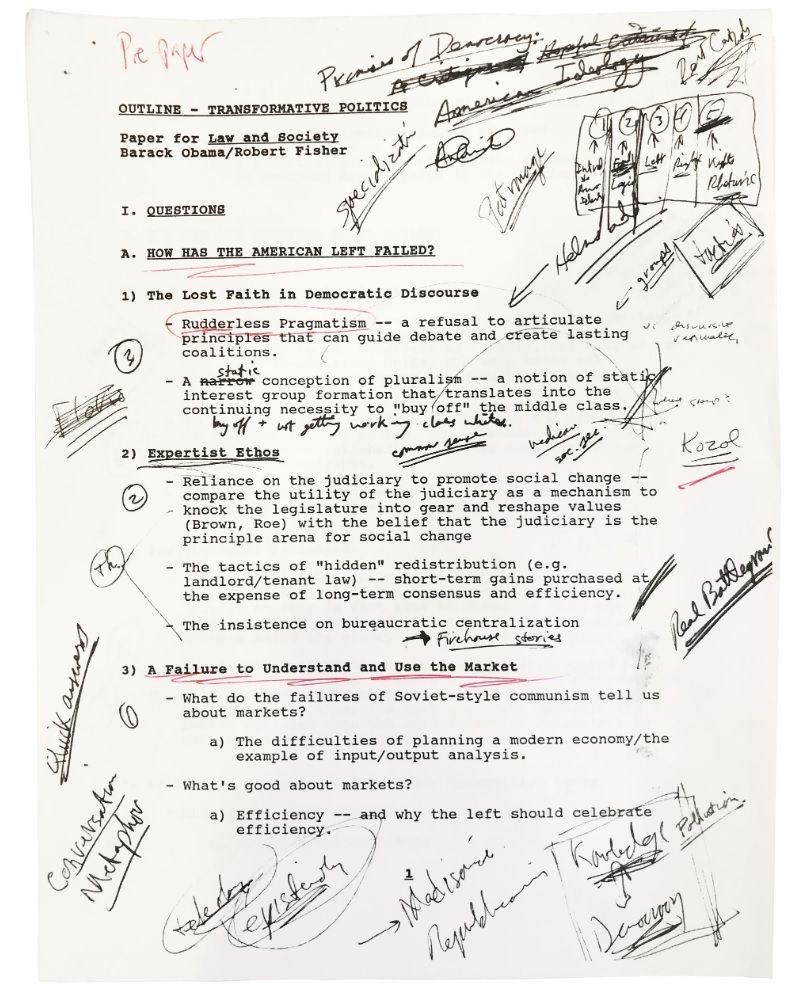

The piece doesn't seem to have much from the manuscript itself, but the material the Times did run — an outline of one portion of the book, focused on critiques of the left — sparked a lot of conversation online. I’m not really on Twitter right now, so I haven’t read too much of it, but I did notice that Obama’s analyses drew a lot of praise from diametrically opposed corners — popularists and anti-popularists, liberals and socialists. It’s possible to read that as a sign these camps have more common ground than they appreciate, but I think it has more to do with Obama’s rhetorical gift, evident even then, for being all things to all people. Substantively, I’m not sure there was much there there. It’s mostly splotches of ink to me. But you can read the outline for yourself below:

Here’s how Shenk frames the impetus for the book:

To understand what Mr. Obama was trying to accomplish with “Transformative Politics,” and why it matters today, you have to start with the problem he was trying to solve. The worldview Mr. Obama brought to Harvard was shaped by his years as a community organizer in Chicago. Driving by shuttered steel mills on his way to ramshackle public housing projects, Mr. Obama came to see deindustrialization and urban decline as two sides of the same broken promise. Chicago was the place where the soaring liberal ambitions of the 1960s — President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream — had crashed into reality, leading to a crisis whose toll was heaviest on poor Blacks. “Every path to change was well-trodden,” he wrote in “Dreams From My Father,” “every strategy exhausted.”

Except one.

The one exception, per Shenk, was cementing what Bayard Rustin called the “March on Washington” coalition — an alliance of blacks, liberals and blue-collar whites brought together by a progressive economic agenda. “According to him, abolishing formal segregation was just the first stage of the battle for civil rights,” Shenk writes. “Securing true equality now demanded a campaign to overhaul the American economy and lift up workers of all races.” And the success of that campaign, Obama argued, would rest upon Democrats “shifting away from race-based initiatives toward universal economic policies whose benefits would, in practice, tilt toward African Americans — in short, ‘use class as a proxy for race’”:

Blue-collar workers of all races, Mr. Obama and Mr. Fisher wrote, “understood in concrete ways the fact that America’s individualist mythology covers up a game that is fixed against them.” But this pragmatic streak also could also be a trap for reformers hoping to bridge the racial divide. “If it has been working-class whites who have been most vociferous in their opposition to affirmative action,” Mr. Obama and Mr. Fisher wrote, “this at least in part arises out of an accurate assessment [that] they are the most likely to lose in any redistributionist game.”

Mr. Obama rejected the idea that appealing to Reagan Democrats required giving in to white grievance. Chiding centrists at the Democratic Leadership Council — headed at the time by Gov. Bill Clinton of Arkansas — he warned against retreating in the battle for civil rights. Moderates scrambling for the middle ground were just as misguided, he argued, as antiracists implicitly pinning their hopes on a collective racial epiphany. Neither understood that bringing the conversation back to economics was the best way to beat the right. Instead of trimming their ambitions to court affluent suburbanites, Democrats had to embrace “long-term, structural change, change that might break the zero-sum equation that pits powerless blacks [against] only slightly less powerless whites.”

Again, this is classic Obama as a matter of political temperament. Everyone’s a little bit wrong and a little bit right — the answers we’re looking for are somewhere in the nebulous middle. You’ll find proponents of “bringing the conversation back to economics” among the followers of both Karl Marx and James Carville; nowhere in the above outline, at least, does Obama offer thoughts on what form the conversation should take. As it happens, Carville’s side won out within the Democratic Party, though not for a want of effort on progressives’ part. Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988 were daring efforts to bring Rustin’s vision to life; the outline suggests Obama would have attributed their failure to Jackson’s unwillingness to divorce himself from the Democratic Party’s identity political factions.

Clinton, conversely, went too far in the other direction by Obama’s lights. Yet he succeeded where other Democrats hadn’t — exit polls in 1992 and 1996 suggest he narrowly won the white working class while retaining the support of black Democrats who backed him even on policies like the 1994 crime bill. And while neoliberalism made ground by bringing the conversation back to economics, that conversation was shaped by a moral infrastructure. Clinton and his peers argued that America’s inequalities, racial and not, could only be rectified by the paternalistic discipline of programs and institutions — from our schools to our courts — reformed to make hard-working, straight-laced, and self-sufficient market competitors out of the downtrodden. Those reforms would be crafted by the very technocratic elites Obama wanted Democrats to cast aside. It should be obvious to all now that this failed as a matter of policy. But as a matter of politics, neoliberalism appeared to work well enough — on the surface and in the short-term — that Obama wound up going along with it for the most part.

Interestingly, Shenk’s piece basically omits the Clinton presidency and its impact on the party; we zoom from Obama’s letter in 1991 to Obama’s Democratic convention speech in 2004:

By the time of Mr. Obama’s star-making turn at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, his policy ambitions had narrowed considerably. But he continued to follow key elements of the game plan outlined in “Transformative Politics.” When Mr. Obama scolded pundits for slicing America into red states and blue states, it wasn’t a dopey celebration of national harmony. It was a strategic attempt to drain the venom out of the culture wars, allowing Democrats to win back working-class voters who had been polarized into the G.O.P. And it elected him president, twice.

That makes what came next even more important. After the 2012 campaign, analysts (misleadingly) attributed Mr. Obama’s victory to a majority powered by young, diverse and highly educated Americans. With Donald Trump on the ascent, moral and political considerations appeared to point away from Bayard Rustin’s March on Washington coalition and toward what came to be known as the Obama coalition — an alliance that doesn’t bear much resemblance to the majority that a younger Mr. Obama envisioned but has become the backbone of the Democratic Party.

I’ve written about this now common misreading of Obama’s electoral record several times now, so I won’t repeat myself at length again. The short version is that Obama’s presidency did essentially nothing to reverse the Democratic Party’s erosion with white working class voters, especially down-ballot. And their losses were attributable, at least in part, to portions of the neoliberal agenda that gradually worsened the deindustrialization of formerly Democratic working-class communities. While the demographic triumphalists were pitifully wrong about Obama’s victories pointing the way toward a permanent, multiracial, and educated electoral majority, they definitely weren’t wrong that educated and minority voters wound up being Obama’s saving grace given his weakness with the white working class, which we’ve evidently decided to retcon. But they wouldn’t carry the party for long.

Who or what will now? Though he isn’t mentioned even in passing, Shenk ends the piece with an endorsement of Bernie Sanders’ campaigns for the presidency:

Yet Mr. Rustin’s vision — the same vision that once upon a time drew a young Barack Obama into politics — remains the best starting point for coming up with a truly democratic solution to the crisis of democracy. Only 27 percent of registered voters identify as liberal. But 62 percent of Americans want to raise taxes on millionaires. An even greater number — 71 percent — approve of labor unions. And 83 percent support raising the federal minimum wage.

Rebuilding the March on Washington coalition requires an all-out war against polarization. That larger project begins with a simple message: Democrats exist because the country belongs to all of us, not just the 1 percent. With this guiding principle in mind, everything else becomes easier — picking fights that focus the media spotlight on a game that’s rigged in favor of the rich; calling the bluff of right-wing populists who can’t stomach a capital-gains-tax hike; corralling activists in support of the needs of working people; and, ultimately, putting power back in the hands of ordinary Americans.

That’s all swell, but if that messaging and those proposals were enough to win on their own, Sanders would be president already. Somewhere, there are pieces missing.

Somewhat relatedly, I went to a brief conference the Roosevelt Institute hosted a few days ago on “industrial policy,” which doesn’t seem to mean much more than active government planning, intervention, and management to achieve particular goals within the economy. It’s a phrase that’s being used more and more on both the right and the left these days, which some have read optimistically as another sign that the neoliberal consensus is collapsing. More concretely, it’s the label some in progressive policy circles have placed upon Biden’s major economic accomplishments so far, and officials from the administration were on hand to celebrate the Inflation Reduction Act, the infrastructure bill, and the CHIPS Act as emblems of a new economic approach. I don’t really think public investment, targeted subsidies, and regulatory reforms are novel tools in liberal and progressive policymaking, but that’s a minor rhetorical quibble. More substantively, UMass-Amherst’s Lenore Palladino, a Roosevelt Fellow, proposed a number of ideas in Boston Review last month that might deepen industrial policy's impact and spur “a broader reorientation of corporate decision-making that outlasts infusions of public money into specific industries and that truly transforms the economy”:

A wide range of guardrails could be implemented, from those that limit extraction, to those that empower workers, to those that ensure the government benefits on the upside while sharing the risks of the downside with private companies. One straightforward step that policymakers implement is ensuring that corporations with stock trading on open markets do not engage in stock buybacks while receiving funds from U.S. industrial policy—especially because no limits currently exist in securities regulation. This approach was taken in the emergency lending programs in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act—companies were simply restricted from conducting stock buybacks or paying shareholder dividends while receiving funds from CARES programs. If such limits are not contained in statute, policymakers can construct lending or grant programs that give precedence to companies that commit to prioritizing investments during the investment period. While this raises critical questions about enforcement if companies break their commitment once the loan or grant has been made, it does incentivize corporate leaders to demonstrate their commitments to innovation rather than value extraction.

One of the express reasons policymakers engage in industrial policy is to support “good jobs.” Public investments should contain project labor and prevailing wage agreements where appropriate, both of which are staples of local and municipal economic development. Any company receiving public funds, whether loan or grant, should commit to union neutrality. Policymakers should also experiment with new ways to incentivize worker voice inside companies.

[...]A public financial investment in a private company could also be accompanied by a public equity stake with rights in corporate governance. This would operate just as financial investments with private financiers, including shareholders who purchase shares on secondary markets and never contribute directly to a firm’s available financial resources. Public equity stakes could mean the federal government receives a variable financial return on an investment. They might also enable involvement in governance, including the ability to veto certain kinds of company actions, and accompany both economic and governance rights. Public equity stakes could be tied to the scale of financial commitment or could be established through “golden shares”—specific types of equity that only grant the government the right to vote on major corporate decisions such as dissolutions or mergers.

While they would apply only to companies drawing major public investments, these proposals would still be major interventions in the realm of corporate governance and capital ownership — a policy frontier Sanders and Warren quietly ventured out on during the 2020 primaries and that I try to explore in some depth in my book. You’re going to hear more and more about ideas like this in general, I think — there’s a growing sense that putting “power back in the hands of ordinary Americans,” in Shenk’s words, will be a matter of actually granting ordinary Americans democratic power within the economy rather than merely correcting or constraining its inequities post facto from without. It’s just very hard to read work like Elizabeth Anderson’s 2017 book, Private Government, for instance, without feeling like this is the way forward for progressive policy and rhetoric:

Consider some facts about how employers today control their workers. Walmart prohibits employees from exchanging casual remarks while on duty, calling this “time theft.” Apple inspects the personal belongings of their retail workers, who lose up to a half-hour of unpaid time every day as they wait in line to be searched. Tyson prevents its poultry workers from using the bathroom. Some have been forced to urinate on themselves, while their supervisors mock them. About half of U.S. employees have been subject to suspicionless drug screening by their employers. Millions are pressured by their employers to support particular political causes or candidates.

American public discourse is also mostly silent about the regulations employers impose on their workers. We have the language of fairness and distributive justice to talk about low wages and inadequate benefits. We know how to talk about the Fight for $15, whatever side of this issue we are on. But we don’t have good ways to talk about the way bosses rule workers’ lives. Instead, we talk as if workers aren’t ruled by their bosses. We are told that unregulated markets make us free, and that the only threat to our liberties is the state. We are told that in the market, all transactions are voluntary. We are told that, since workers freely enter and exit the labor contract, they are perfectly free under it: bosses have no more authority over workers than customers have over their grocer. Labor movement activists have long argued that this is wrong. In ordinary markets, a vendor can sell their product to a buyer, and once the transaction is complete, each walks away as free from the other as before. Labor markets are different. When workers sell their labor to an employer, they have to hand themselves over to their boss, who then gets to order them around. The labor contract, instead of leaving the seller as free as before, puts the seller under the authority of their boss. Since the decline of the labor movement, however, we don’t have effective ways to talk about this fact, and hence about what kinds of authority bosses should and shouldn’t have over their workers.

Part of the answer here is obviously shoring up the labor movement. But there’s also new ground to be broken with policies like codetermination, inclusive ownership funds, and social wealth funds which, at any rate, are more interesting to debate and mull over than the question of which version of the Democratic Party’s past we ought to return to. We're here because all previous versions ultimately lost. And I doubt we’ll find our way to a “transformative politics” without advancing ideas we haven’t yet tried.

A Song

5’O Clock World - The Vogues (1966)

Bye.

Nwanevu. Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.